Film is a remote medium. We long to feel close and connected to filmic action, especially when it comes to movement. I’ve come to believe that film as a medium desires - even seems to require - a semblance of story. And the face is the locus of storytelling on film. This is not true of live dance, where form, shape, energy, rhythm and speed can be equally important to meaning-making.

Because of that remoteness, I kept wondering how I might make space for the camera - as a proxy for the viewer - to enter into the intimate world between the dancers; the space that is always important in my stage work…the relational space between people. This is the space of heartbeat, breath, animal senses, desire, power play, and, of course, eye contact or the deflection of eye contact.

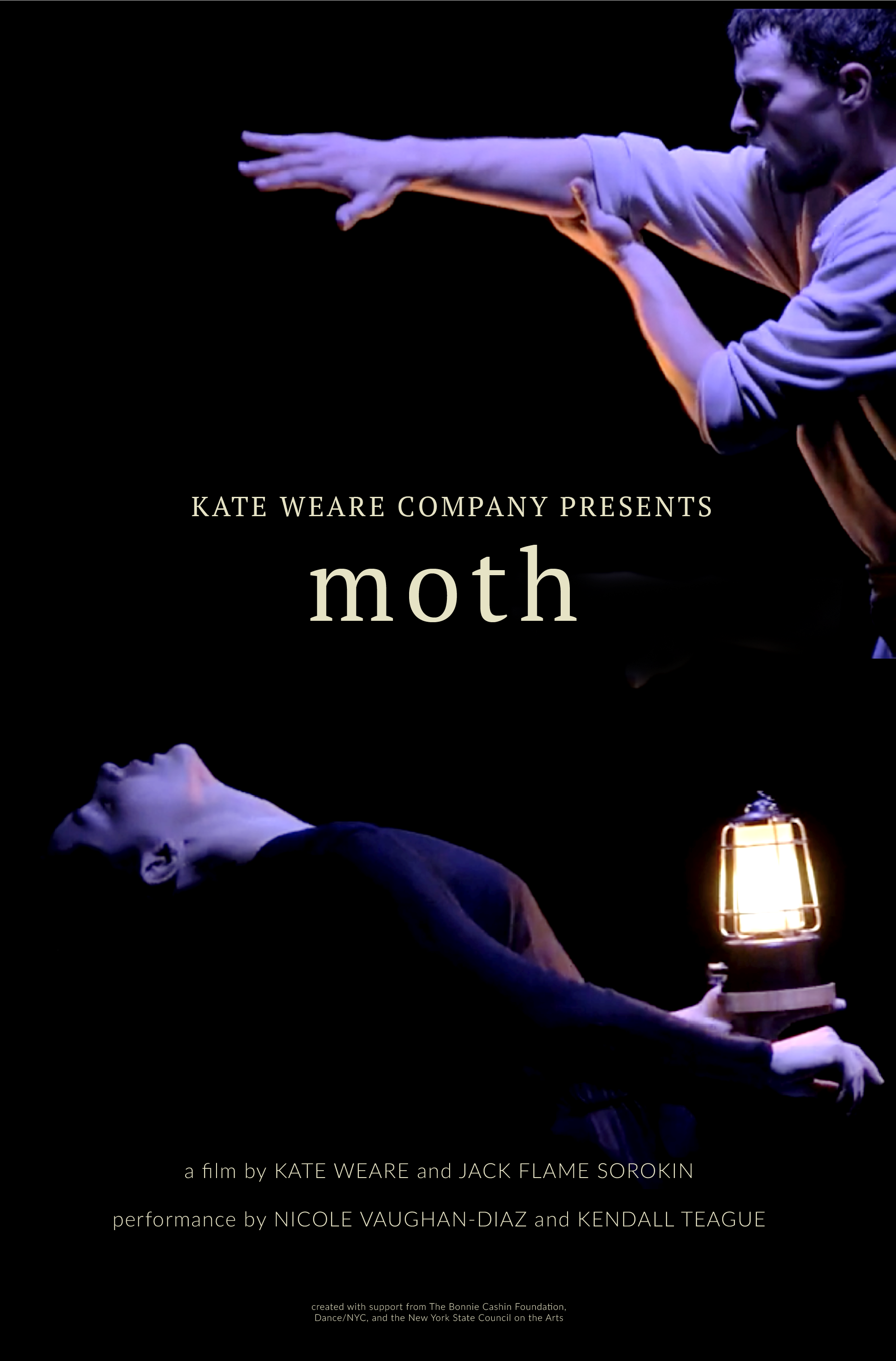

So I decided to choreograph Moth with empty space between movement ideas, far more than would have made sense onstage. Onstage, empty space can become a blackhole, an enervation, if not used skillfully. In live performance, we hold the eye in the wild, so to speak, earning attention when attention is warranted. But in film you can put the eye precisely where you want it with god-like control.

Because the goal of my work is always intimacy, I wanted the camera (the viewer) to have access to the dancers’ faces, like a fascinated voyeur who can’t keep from staring, or an interloper who’s emotionally involved. I built in long moments when the dancers look at each other, or when their faces are in proximity for a period of time; long enough for a camera to roam.

I emphasized foreground and background while shaping the dance, thinking this could be interesting for a camera. The choreography of Moth, danced live, darts forward and back along a straight line; there are circles but they act as tight whorls on a tightrope.

In our final cut of Moth, my choreographic forethought comes through in certain ways, and not in others. Jack and I spend most of the film-time tight to the dancers’ faces, neck and chests in our final cut, dropping all fancy leg and footwork to the editing floor. For me, it’s deeply fascinating how editing makes certain things matter: and how the filmmaker makes this choice for the audience.

Although my artistic instincts are still tuned to the hot-blooded world of dance, each time I make another film I absorb more of its multi-toned, technological, preordained realm. It feels like a limitless world to me, still cool to my touch, but beckoning like a siren song.

In creating our first film, Landfall, my collaborator Jack Flame Sorokin and I played in an exploratory way with environment, energy, movement and composition in the camera’s eye. I came away with two big insights. One: choreography comes alive in editing. Two: do too much in front of the camera and you close down what the camera can do in response.

In creating our first film, Landfall, my collaborator Jack Flame Sorokin and I played in an exploratory way with environment, energy, movement and composition in the camera’s eye. I came away with two big insights. One: choreography comes alive in editing. Two: do too much in front of the camera and you close down what the camera can do in response.